Inflation is the decline in purchasing power of a currency resulting from the increase in prices of goods and services.

It is a very important metric to keep track of when thinking of investment strategies, because in periods of unstable inflation, it can affect the returns of stock investments both in nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) terms.

Why does it affect investing?

As inflation increases, companies need to adjust their prices in order to keep the same level of profitability. Some companies have smaller pricing power and are unable to adjust effectively, leaving them with possibly increased costs but decreased revenues.

On the other side of the coin, we have the consumers, who have the hardest time adjusting their wages to inflation which translates to a reduced ability to purchase more items, which directly affects profits from the source. Consumers usually adjust for inflation, by changing their purchasing preferences, usually by downgrading the quality of products they buy. Think Craft beer vs Light beer. In periods of higher inflation consumers will downgrade from a quality product to a budget product or completely remove the product from their basket. Incidentally, this is one of the core problems with tracking a standard basket of goods as a measure for inflation - consumer preferences change!

I came across this concept initially from Pia Malaney and warmly recommend you check it out HERE.

Where can we see Inflation?

There a number of ways we use to measure inflation. The Federal Reserve of the USA keeps track of a few important metrics such as the Consumer Price Index, the Breakeven Inflation Rate and the GDP Deflator.

CPI - Consumer Price Index

The CPI is a followed basket of goods that measures how prices change over time. Absolute prices are indexed, but we are usually interested in the monthly percent % change from a year ago as a way to measure inflation.

In other words, how do prices change month by month, in comparison to 12 months ago?

The CPI index has multiple sub-categories which track different baskets of consumer goods. The most popular categories are the full CPI and the CPI Ex. Food & Energy, also known as the "Core CPI". The change in Core CPI may have wider implications for an economy as both businesses and consumers feel the price changes of more durable goods and that affect revenues and profit margins.

In the graph below you can see the relationship between the full and core CPI, as well as the money circulating in an economy measured by the M2 money stock indicator.

Relationship between the CPI and the Money Stock (M2)

The Money stock is a (cleaned up) measure of the money in circulation.

By converting it to a % change from the previous year, we can see how much money the federal reserve has injected (not all money is printed) into the economy.

If we were to see the relationship between money in circulation and inflation, we get a negative or non meaningful correlation.

HOWEVER,

My hypothesis is that inflation follows money after some period of time, because it takes a while for firms to adjust the new prices to the money supply.

I tested this by correlating the inflation as measured by the CPI, with the money stock incrementally set back buy one month. In other words, what is the correlation of inflation with the money injected in an N number of months back.

As we start going back in time by one month (left column), we see that the correlation increases and peaks at about 12 and 18 months prior.

Meaning that the money injected 12 and 18 months ago are showing up as inflation TODAY.

The chart below shows the average lagging correlation between M2 and CPI for all items:

This is preliminary evidence that the injected money in an economy show up as inflation later on.

As to answering the question of how much of this factor is accountable for the increase of inflation. My regression analyses yielded an R^2 between 45% and 60% (depending on the used sample size). Lets be cautious and go with the lower estimate.

We can assume that the increase in money supply accounts for 45% in the change of inflation 12 to 18 months after the fact.

If this is true, than we can expect to see 4% to 6% levels of inflation (as measured by the CPI) in the following months. This increase will affect markets and investors should incorporate it into the pricing and investment strategies.

A question has arisen, whether this phenomena will be transitory. For this to be transitory, 2 things must hold:

Inflation can be controlled after the injecting stops

The injecting actually stops

Stories of both a transitory inflation and new infrastructure projects are internally inconsistent.

Click HERE to see the full dynamic excel matrix.

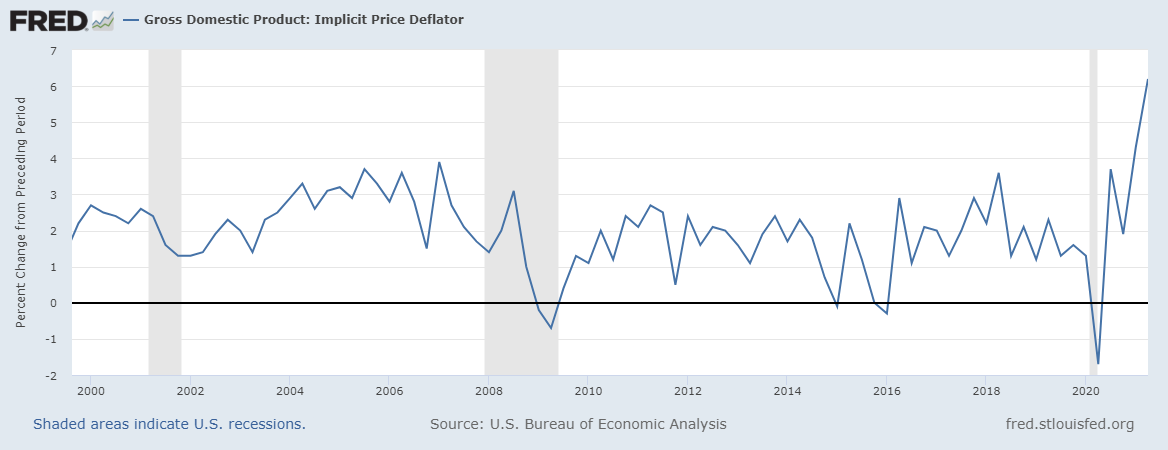

GDP Deflator

Instead of indexing a basket of goods over time, the GDP Deflator looks at the economic output and measures how much of the growth is due to changing prices.

The measure is again expressed in percent, and it is reported by the Federal Reserve on a quarterly basis. You can find it HERE.

Implied Inflation

Implied inflation is the expected inflation of the economy in the long term. It is forward looking and shows us our estimate of what will inflation look like in the future. A good starting point is to see the 10-year and 5-year implied inflation also known as the breakeven inflation rates.

Now we need to look at what is contained in the implied long term inflation. For that we need to take a step back and look at the risk-free rate.

Put simply, the risk-free rate is the expected rate of return on a long term investment with no default risk. A proxy for this rate is the US economy as it holds an AAA rating and if you agree with that notion you can think of the risk-free rate as the rate for a long term investment in the US Economy. A long term measure is considered something that is 10 + years.

So, how do we get from the return of investing in the US economy to the implied inflation?

Within the risk-free rate there are 2 main drivers. The first one is the expected growth of an economy, and the second one is inflation. The logic behind this is that investors will not pay for a long term bond with a lower rate than inflation and the growth of an economy. This is the minimal return a treasury must offer in order to sell bonds.

OK, so the Risk free rate is driven by growth and inflation. Now we need to separate the two, in order to see what is the expected inflation for an economy.

Luckily, mature markets like the US, also issue bonds that change with the price of inflation. These are called Treasury Inflation Protected Securities or TIPS.

In order to get expected inflation, we simply take the TIPS rate and subtract it from the risk-free rate. With this we have effectively separated the implied growth rate and implied inflation rate for an economy. I use the term implied because the prices of these securities are auctioned to brokers, and are not set arbitrarily.

Specifically, the TIPS interest rate is determined by auction. The change in principal is tied to inflation as measured by the CPI. So we can see how the two measures are connected.

In the chart below, we can see the long term implied inflation rate and all of it's components.

Now we can adequately interpret the chart. What we are seeing in effect is:

The estimated real growth of the US economy in the next 10 years, indicated by the TIPS rate.

The difference between the 5 and 10 year implied inflation rate - indicating that markets expect a larger short term volatility.

And the fact that the return on a risk-less investment in the US economy is mostly driven by inflation rather than growth. This phenomena may lead to stagflation which is just the presence of inflation with no real growth.

Thank you for reading!